Climate is defined as a pattern of precipitation and temperature over years. Drought is an aspect of climate and is defined as decreased rainfall leading to a shortage of water. A deluge of rain can cause flooding, but the overall rainfall can still define that time as a drought. Drought comes in cycles, some lasting much longer than others. For example, the people of Mesa Verde experienced 23 years of drought before they left in 1300. A 50-year drought led to the abandonment of Chaco Canyon between 1140 and 1150, with the population moving to areas with more reliable water for farming. Many of the pueblos along the Rio Grande were established at that time. Since drought comes in cycles, it leaves us constantly optimistic that change for the better is ahead. But is it this time?

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) was formed in 1970 from a loose grouping of climate agencies across various U.S. government departments. Data which had been collected as early as 1807 by volunteers was now available in one place to study trends in climate. Heat and rainfall data from 1895 to present were incorporated into the Palmer Drought Severity Index, a formula for calculations of severity which factor in both heat and rainfall. In 2020, NOAA began a graphic index displaying drought at five different levels with D 0 being abnormal short-term dryness and D 4 being the most severe with widespread loss of crops and pasture. Some climatologists think we in the mid Rio Grande are currently in a drought cycle which began in 2001. Why are our trends troublesome?

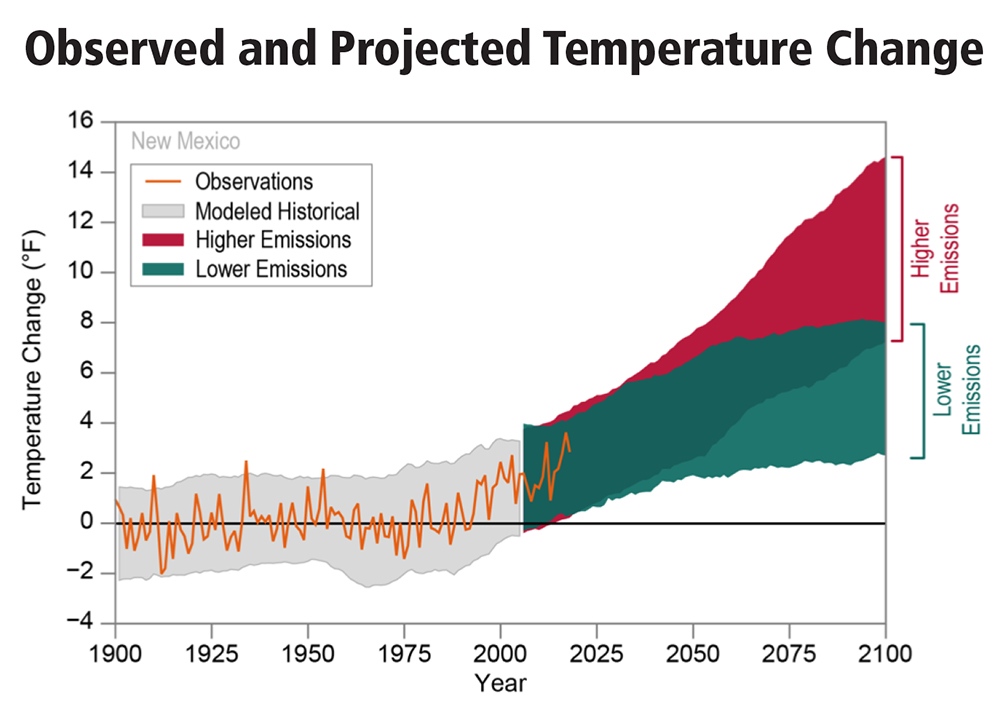

New Mexico’s average annual temperature has increased by three degrees over the past 50 years. Higher temperatures increase evaporation of soil moisture; normally this has a cooling effect, but when the heat is prolonged and the soil moisture depleted, the land warms even more and causes heat waves which in turn makes the drought worse. This is called a hot drought.

Drought means lack of predictability of precipitation, so responses have focused on controlling the timing of water delivery through various means, including dams, irrigation, acequias, wells, cisterns, and cloud seeding. Since there is only a finite amount of potable water globally, desalination – turning saltwater into fresh water – is another potential mitigation measure for those with access to ocean water. Israel is an example of a country that has significantly invested in desalination plants.

Living along a river should provide us with enough surface water to meet our needs, but currently those of us living in the mid Rio Grande are becoming more dependent on water pumped out of the Ogalala Aquifer. An aquifer is an underground lake, also referred to as ground water. Relying on the Ogalala Aquifer is not sustainable as there is not sufficient rainfall or snowpack to recharge it. The Albuquerque Water Authority (ABCWUA) recharges the aquifer to some degree using treated waste water. The amount of water in the aquifer is measured by monitoring wells scattered around the mid Rio Grande watershed.

The situation around available surface has become worse. In 2020, there was not enough water to supply the irrigation needs of farmers in the mid Rio Grande basin “to prevent catastrophic losses.” Since July and August are critical months for crops like chili and corn which need water to mature. The Rio Grande Compact states of Colorado and Texas agreed to let New Mexico “borrow” some of their state’s stored water from the reservoir at El Vado dam for our “emergency” use to “prevent catastrophic losses” to that year’s agriculture crops. This became an additional debt of billions of gallons of water.as we were already behind in the amount of water NM is to deliver annually to Texas. The compact caps how much water New Mexico can be borrow from the reservoirs at El Vado, Cochiti and Elephant Butte over a set time. New Mexico has reached that cap. And because of the continual drought conditions, El Vado is at 8% and Elephant Butte, is now at only ten percent of capacity.

As we face these grave facts, it’s important to also acknowledge that any new approaches to drought mitigation and climate change should not be at the expense of racial or economic minority communities which have historically taken the brunt of polluting industries, roadways, and are located in areas which are more prone to flooding.

What are possible solutions? We can move to a northern city along a vital river with more rainfall, or we can stay here and look for ways our community can mitigate this problem. The first step is to recognize that we live in a desert, are experiencing a hot drought, and are in the midst of climate change. While we can’t prevent drought, we can be vigilant and follow practices which conserve water.

Some ideas for individuals and the community:

- Decrease our personal use of water (the average American uses 82 gallons water/day at home, much of this on tasks such as flushing, showering, and washing dishes and clothes). We can take steps to reduce this by increasing sponge baths instead of showers, repairing any water leaks, installing low flow toilets, and replacing faucets and shower heads with more water efficient appliances.

- Look for workshops by garden groups and nurseries on xeriscaping – landscaping that promotes water efficiency by using native and adaptable plants.

- Check out the ABCWUA website for rebates on water saving washing machines, xeriscaping, and other conservation measures.

- Go to the City of Albuquerque’s website for a list of more drought-tolerant trees and shrubs recommended for this area.

- Join up with a group doing community actions which promote sustainable practices, such as planting native trees, shrubs, and grasses. (See Community Actions on the menu bar )

- Advocate for city planners to conduct a heat mapping – to map the parts of our city which are hottest (urban heat islands). These areas should become a priority for increasing green space (parks) and tree planting. There may be a need for some building code changes as well.

- Maintain the vegetation we have now using techniques promoted by permaculture.

- Decrease use of concrete or asphalt for surfacing. Pavement retains heat, making Albuquerque 5-8 degrees hotter than surrounding areas.

- Look at projects other communities have adopted. For example, Tucson requires grey water plumbing in new construction. China’s Great Green Wall project was begun in 1970 to interrupt desertification and sequester carbon; today, it has planted 66 billion trees, decreasing dust storms by 20%. Another “green wall” has been started across Africa. What about one across Albuquerque?

Add your ideas to the comment section below.