by Anita Amstutz

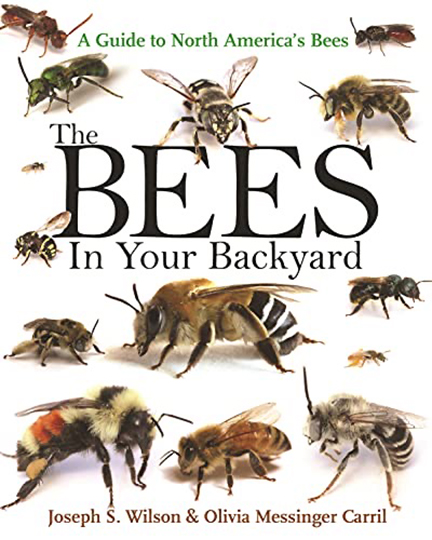

Recently I sat down for an interview with Dr. Olivia Carril, co-author of the beautiful compendium, The Bees in Your Backyard: A Field Guide to North America’s Bees. Olivia lives in Santa Fe with her family and is a national treasure with her depth and breadth of knowledge about wild bees, having studied and done field research for over 25 years.

Olivia grew up in a family that valued being outside, and she chose to study biology so she could be paid for being in nature and doing what she loved. Initially she thought she’d follow the track of flowering plants, but then she landed a job in a lab studying bee specimens already organized with their pins in drawers—bees from Poland to Zimbabwe to North America. Esteemed research entomologist Dr. Terry Griswold noticed her fascination and enthusiasm, and she landed her first project in central/western California. There, Olivia documented bees landing on flowers and became curious about the unique symbiotic relationship of bees and flowers, noticing patterns in how bees were drawn to certain plants at specific times of day and exploring the importance of colors, scents, and shapes of flowers.

Olivia realized she loved not just organizing wild bees but also exploring and stalking them. She and her family settled in the high deserts of the Southwest so she could research her specialty in bees and their co-evolved landscapes.

Co-Evolution of Wild Bees and the New Mexican Landscape

North America has over 4,000 species of wild bees; of these, at least 1,000 are indigenous to New Mexico! This is what makes New Mexico such a fine place to study wild bees. Because we have many bioregions, including some warmer southern climes that have longer flowering seasons, it’s a great place to Bee! Wild bees like warm soil and dry climates so their ground nests don’t get moldy. These microclimates, which have evolved different niches and flower species, have in return caused adaptations in bees of body types and antennae. Thus, wild bees have evolved here in unique ways.

In the desert, the most critical pollinators of flowers and wild landscapes are the wild bees which have co-evolved with them. Dr. Carril reminds us that in the desert, it’s the wild bees who are most responsible for pollination. For instance, two mason bees are more efficient pollinators than 100 honeybee workers! And think about this…they are independent, free agents! No need for management. Now you may meet some of them!

Some of Our Native Bees

Dr. Carril took me on a magical whirlwind tour of five of her favorite superstar bees. She began by stating, “Wild Bees are like the most chill person you’ve ever met. They are resilient, able to adapt and roll with the punches. Invasive weeds? No problem! Disturbed ground? Sure, I can make a nest there.” This immediately endeared me to these fascinating creatures from the winged queendom.

The first bee she introduced to me to was the family Diadasia with 45 different species. Dr. Carril calls them the “flying teddy bears.” She showed me a blond fuzzy bee body with cathedral gossamer wings. They have evolved as specialists on the native plant species globe mallow, who petals you can peel back at dusk to see the males sleeping in the orange flowers.

Another favorite is from the family of Halictidae, also known as sweat bees. These striking little bees are green/gold with irridescent metallic bodies. One of their family members may lick your sweat, but most don’t. They are generalists, collecting pollen from both invasive and native plants.

Then there are the mason bees, from the Megachilidae family. They have large eyes and thick heads with a muscle for their strong mandibles to manipulate mud in building their nests. They have beautiful aquamarine metallic bodies.

The honeybee-sized mining bees, family Andrenidae, are diggers, solitary ground nesters with stout furry bodies. They are specialists in orchard crops, plants in the pea family, sunflowers, penstemon, and astragalus

Finally, my favorite, the fairy bees, of the genus Perdita, which are specialists on creosote bushes. Less than a millimeter in size, they are so tiny you can easily miss them.

Challenges for the Wild Bee

In terms of the challenges, Dr. Carril said, “We don’t know enough to know how our bees are doing.” On of the biggest problems is their elusive nature. We know it’s bad for bees to put a parking lot where cactus and creosote used to be, but it’s challenging to stalk those populations that move when their habitats are destroyed.

Olivia said that one of her biggest questions in New Mexico is not about pesticides and agriculture changes, but rather the placement of honeybees that compete in areas of native bees. Every month of the flowering season she collects data from standardized plots to try to explore this question, as well as to understand cattle grazing disturbance of wild lands, uncharacteristic burns, and habitat fragmentation from oil and gas development.

In the end, Olivia left me with more questions about wild bees and a desire to learn more. Humans are waking up to the fascinating world of wild bees and learning to live in relationship with them and their habitats. We are learning how the whole web of life is woven together in a seamless whole, that when one little piece of it changes or breaks down due to human activity, it can impact the whole. The good news is that more and more people are stepping up to speak for the bees!

Thank you, Dr. Olivia Carril, for your dedication to chasing the wild bee and taking time to share your love of bees with us.

Post script: Wild bees do not make honey for human use. They play a critical role as polinators for our ecological health.

I’m glad you published this piece on bees and I too am left with questions: do the bees featured here have anything to do with honey creation? Or is their contribution focused entirely on pollinating desert plants which would not reproduce without bee assistance? I know a woman who has nine hives hidden in the Sandia foothills and sells delicious honey from her hives; she too fears the competition from aggressive honeybees. Nature’s complexity continues to astound.

Esther, wild bees are purely for pollinating our ecosystem. They do not produce honey for humans which is one reason why humans don’t understand all the fuss to protect them. Just because they are not utilitarian for human needs they are indispensable for a healthy and balanced habitat and good system!

Anita, thanks for this article. I actually read it all (as opposed to scanning). I first became aware of wild bees from reading Bee Time, which I recommended to you, and was glad to add to my knowledge. I’ve become more aware of wild bees and have seen them in action around my yard. I’m going to have to see if there are “teddy bear bees” sleeping the the Globe Mallow around my house. -Glen

What is the meaning of the genus name “Perdita” for fairy bees?

Perdita is the genus name. I know that in Spanish it means little lost girl. Have no idea how it became the genus name for Fairy Bees. I’ll do some more checking.