by Anita Amstutz

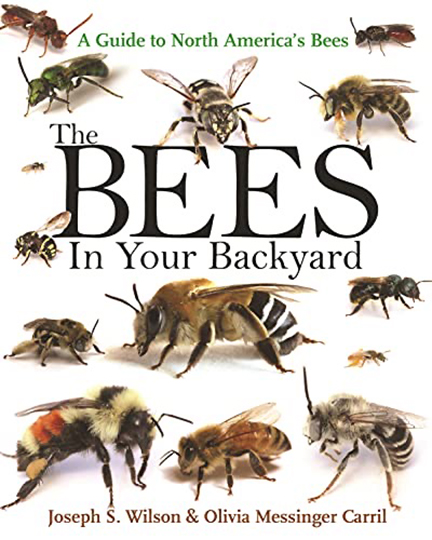

Recently I sat down for an interview with Dr. Olivia Carril, co-author of the beautiful compendium, The Bees in Your Backyard: A Field Guide to North America’s Bees. Olivia lives in Santa Fe with her family and is a national treasure with her depth and breadth of knowledge about wild bees, having studied and done field research for over 25 years.

Olivia grew up in a family that valued being outside, and she chose to study biology so she could be paid for being in nature and doing what she loved. Initially she thought she’d follow the track of flowering plants, but then she landed a job in a lab studying bee specimens already organized with their pins in drawers—bees from Poland to Zimbabwe to North America. Esteemed research entomologist Dr. Terry Griswold noticed her fascination and enthusiasm, and she landed her first project in central/western California. There, Olivia documented bees landing on flowers and became curious about the unique symbiotic relationship of bees and flowers, noticing patterns in how bees were drawn to certain plants at specific times of day and exploring the importance of colors, scents, and shapes of flowers.

Olivia realized she loved not just organizing wild bees but also exploring and stalking them. She and her family settled in the high deserts of the Southwest so she could research her specialty in bees and their co-evolved landscapes.

Co-Evolution of Wild Bees and the New Mexican Landscape

North America has over 4,000 species of wild bees; of these, at least 1,000 are indigenous to New Mexico! This is what makes New Mexico such a fine place to study wild bees. Because we have many bioregions, including some warmer southern climes that have longer flowering seasons, it’s a great place to Bee! Wild bees like warm soil and dry climates so their ground nests don’t get moldy. These microclimates, which have evolved different niches and flower species, have in return caused adaptations in bees of body types and antennae. Thus, wild bees have evolved here in unique ways.

In the desert, the most critical pollinators of flowers and wild landscapes are the wild bees which have co-evolved with them. Dr. Carril reminds us that in the desert, it’s the wild bees who are most responsible for pollination. For instance, two mason bees are more efficient pollinators than 100 honeybee workers! And think about this…they are independent, free agents! No need for management. Now you may meet some of them!

Continue reading