Otowi is a word in the Tewa language meaning ‘place of noisy water. This place is on the ancesteral land of the San Ildefonso people. In 1889, the U.S. Geologic Survey choose Otowi as the location of its first national stream gauge with the purpose of determining if adequate water was available in the New Mexico Territory for irrigation purposes and if the government should encourage new development and westward expansion. They decided to go ahead with expansion, and the Otowi Bridge gauge near where the Rio Chama flows into the Rio Grande remains a major measure for water law. Sixty percent of the water passing the Otowi gauge has to be delivered to Elephant Butte, which by compact, is considered the delivery point of water to fulfill New Mexico’s obligation to Texas.

But what is a compact? Every time water crosses a state line, a compact, similar to a treaty, is written and ratified by congress. New Mexico is part of eight different compacts. In 1938, the state legislatures of Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas signed off on our largest compact known as the Rio Grande Compact. The purpose was to “equitably proportion water in the Rio Grande basin and to remove causes for present and future controversies.”

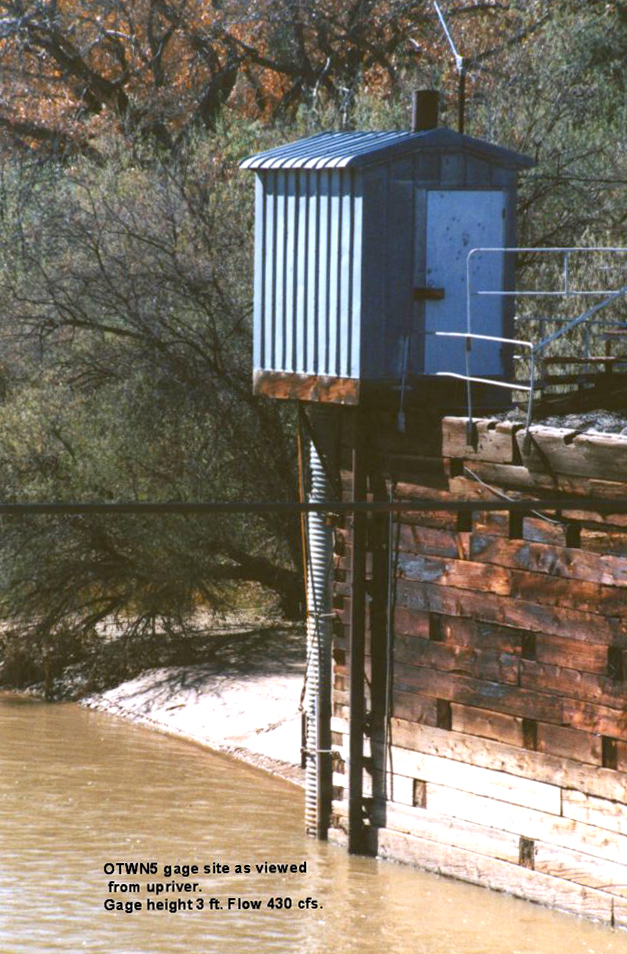

The U.S. Geologic Survey placed index markers (gauges) at intervals along the river so they could monitor the flow of water downstream. New Mexico is to deliver 12 billion gallons of water to Texas each year but we have struggled to do so. The trend over the past 10 years shows us falling behind. Currently we are about 100,000 acre feet in arrears. (One acre foot is 326,000 gallons of water.) When the debt reaches 200,000 acre feet we will violate both state and Federal laws. In other words, there are consequences.

To make matters worse, in 2020 there was not enough water to supply the irrigation needs of farmers in the mid Rio Grande basin “to prevent catastrophic losses.” July and August are critical months for crops like chili and corn which need water to mature. Colorado and Texas let New Mexico borrow water stored behind El Vado dam. This “emergency” became an additional debt of billions of gallons of water which NM already owes to TX. The compact caps how much water New Mexico can borrow from the reservoirs at El Vado, Cochiti and Elephant Butte over a set time period. In the mid Rio Grande, we will soon reach that cap.

Our water future may become more complicated by the fact that the Supreme Court is now hearing the case Texas vs. New Mexico. Texas has charged that NM has been pumping ground water (which is connected to surface water) and not delivering sufficient water to their state according the agreed upon compact. Elephant Butte where Texas’ water is stored is only at 2% of capacity. A ruling may come in the summer of 2021 unless the states can negotiate a compromise. The latter would be preferable as all would get something rather than winners and losers.

Data from the 34 gauges between Otowi and Elephant Butte are now in real time and transmit electronically to USGS to measure water flow. This information can be used for water management in smaller areas of our watershed. So, what is the Otowi gauge saying to us at this time?

In the 160 miles of river in the mid Rio Grande watershed, there are many acequias irrigating Native and Hispanic farmers’ fields and orchards, habitats for countless plants and animals, domestic wells, and the homes of half of New Mexico’s population. The Bureau of Reclamation recently invited many of the user groups to participate in The Rio Grande Basin Study. The groups will offer plans to mitigate the problems they see. The Bureau will then model those in an attempt to develop an overall strategy for a sustainable and resilient water future using available science, planning and management. The Middle Rio Grande Water Advocates vision is for a resilient and sustainable water future. There website has current information on the Basin Study.

In the meantime, The Mid Rio Grande Conservation District will have to decide how to pay New Mexico’s water debt. About the only tool they have is to shorten the irrigation season which will definitely affect the number and types of crops planted in the future.

Nice article. Being involved in NM water issues for a few decades. I fully agree that sorting out the big picture is a giant challenge. We engineers can handle some of the the more-contained tasks.

A point or two worth mentioning.

NM has always been ahead of our neighbors in tying together our internal water management. For a long time, some states ran one set of books on surface water and another set of books on groundwater, but didn’t tie the two together. Steve Reynolds, the State Engineer (which in NM means water) from I-don-know-when until the 80s was akin J. Edgar Hoover in the FBI. He decided what needed doing, no governor could trump him, and he decided fairly comprehensively and impartially.

Conflicts with other states, however, turn on legal points more than hydrology. Today’s challenges largely exist because, as the article suggests, the attorneys didn’t understand the hydrology when they set the compacts in stone. Don’t blame global climate change (though it may play a part); the original data was simply too sparse.

I represented NM on a compact that at the time was 30 years in settlement. We engineers representing all players could probably have worked out something reasonable in a year or two if we’d been able to expel the attorneys. But. alas, they ran the show.

As for mention of the MRGCD, they’re just one of the irrigation districts. How to pay NM’s water debt isn’t their call. The heavyweights are likely the State Engineer, the Bureau of Reclamation and the Corps of Engineers, the latter two operating the reservoirs under a myriad of purposes.

Dick,

Thank you for the history you provide here. Your final point on whose overall call it is is true. The MRGCD gives us living here a local look and what is happening and some of us have a vote in this locally. The Bureau of Reclamation is now looking for local input into a Water Basin plan they will be advancing in the future for our water. More on this in another issue.