Heat islands are found in urban areas that experience higher temperatures than outlying areas – the difference can be eight to ten degrees Fahrenheit. The sun’s rays are absorbed by buildings and particularly black asphalt. Heat islands are formed where greenery is limited and there is increased density in housing. These conditions are often found in areas of low-income housing.

Heat can cause exhaustion, swelling. cramps. and even death. Heat is the leading weather-related killer in the US, with a related death rate from 0.5 to 2.0 per million between 1979 and 2018. Heat-related deaths (when body temperature exceeds 104℉) and heat-related illnesses (HRI) are almost certainly under-reported. At-risk populations include people with incomes below the federal poverty level who have fewer options to be safe during a heat wave, older adults who may have underlying illnesses, the very young who are dependent on others to keep them cool and hydrated, and people with disabilities who cannot get to cooler places. The EPA has an informative booklet on Heat Islands.

In New Mexico, the Department of Health’s Division of Epidemiology keeps our state’s data. New Mexico is warming faster than originally predicted and is the second fastest warming state in the US. The number of days of statewide average temperatures greater than 90℉ is growing at the rate of one day per year, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; it is predicted to be 104 days this year.

Heat waves have various regional definitions, from temperatures hotter than the historical average for more than two days to temperatures greater than 90℉ for five days to a series of days with temperatures greater than 100℉. Using any definition, heat waves are predictable with today’s weather tools. So how do we prepare to help our most vulnerable living in Albuquerque’s heat islands?

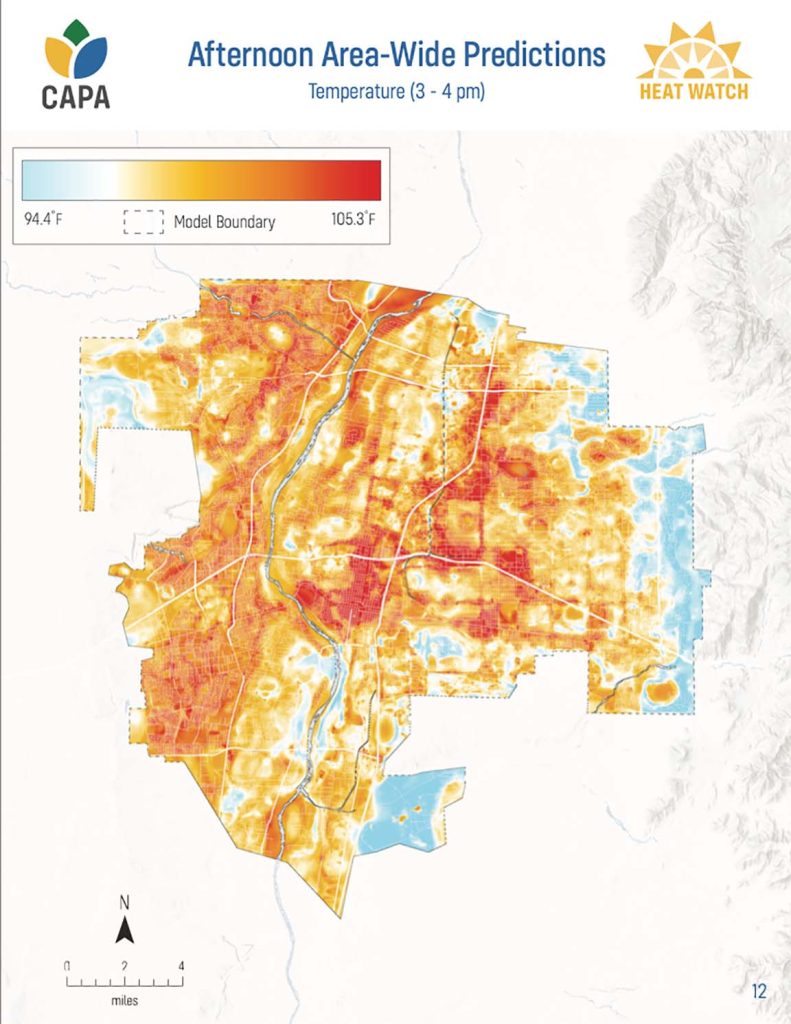

The city of Albuquerque contracted with CAPA Strategies to do a city-wide study of heat at two different times of day and at locations along heavily-trafficked and public-transportation routes. Volunteers walked, rode bikes, or drove over assigned routes using standardized equipment to record measurements. The amount of heat was rated from high to low and mapped out.

Unsurprisingly, the most heavily trafficked streets and intersections were the hottest, especially along corridors adjacent to I 25 and I 40. While there are heat vulnerabilities in many places in the city, downtown. Wells Park, and the International District tend toward greater heat. The city environmental department and some other branches of city government are meeting monthly on this problem, but the only ideas made public at this time are planting more trees and the consideration of cool pavement coatings for heavily-used streets.

When will we learn more of the city’s plans, especially as they relate to needed changes in building codes and to emergency protections such as cool shelters for the vulnerable during heat waves? by Sue Brown